When I was 12, I escaped the horrors of war in my country, Nicaragua, by illegally emigrating to the United States. I was not alone. Between 1981 and 1990 more than 1 million Central Americans sought political refuge in the U.S. from the civil wars and violence that plagued Nicaragua, El Salvador and Guatemala. From an early age I understood the consequences of intolerance, fanaticism and ideological fundamentalism. I also learned that the absence of responsible political leadership destroys communities and families.

I left my country without my parents, but I still could count myself lucky to be alive.

According to conservative estimates, 150,000 lives were lost in Central America during that tragic decade. In Nicaragua, the exact toll has never been officially revealed by authorities, but objectively speaking it can probably be calculated at around 35,000 dead. Recently, a declassified secret report of the now extinct East German Stasi secret police revealed that Sandinista authorities had reported 19,000 victims between 1980 and 1986. This is a chilling statistic for a country of only three million inhabitants at the time. To put this figure into perspective, it is equivalent to the United States losing 3.5 million lives in one war.

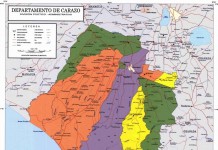

I was born in 1976 in the North of Nicaragua in one of the poorest zones in one of the poorest countries in the hemisphere. In spite of belonging to a middle-class family (my father was a social worker and my mother a small business owner) the revolution of 1979 and the later civil war devastated my family’s finances. The civil war that followed also hit my family beyond the shortages of food and goods. Poverty and need in the war zone didn’t discriminate; middle-class and poor children suffered the same. I was perhaps slightly more privileged— I always had more than one pair of shoes and at one time I even owned a bicycle—but only slightly.

Revolutions and wars also take tolls in ways that are difficult to gauge. As a student, my father was tortured and imprisoned by the Somoza regime, and when the Sandinistas took power, my mother´s small business was taken over by the new Marxist-Leninist authorities, leaving her bankrupt. Both of my parents suffered in different ways from the polarization of Nicaraguan society at the time. The situation worsened after my father´s accidental death in 1985. He was not yet 33 years old.

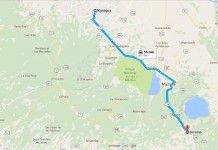

Due to the intensification of the war, in which both the Sandinistas and Contras were actively recruiting children and adolescents soldiers, my mother made one of the most difficult decisions a mother can make. Unable to obtain permission to emigrate to either the U.S. or Canada, she arranged for my illegal passage north through Guatemala and Mexico to the U.S., where I landed in Brownsville, Texas.

I remained in the U.S. until 1990, when the long process of peace negotiations culminated in the first free elections in the history of Nicaragua, and allowed me to return. National Opposition Union (UNO) candidate Violeta Chamorro Barrios’s victory in 1990 ended the war. I found a country still deeply divided, but like many Central Americans who returned from exile, I was passionately hoping for a fresh start. The “Generation of the 1990s” was imbued with the same optimism felt by young people around the world who lived through the close of the Cold War and the collapse of totalitarian regimes in Europe. A new era of information and innovation seemed about to begin.

One of the most significant results of this change was a generational withdrawal from politics. In contrast to the deep political involvement of young people in previous decades, an emerging interest in technological innovation, the accumulation of wealth and entrepreneurial achievement gave rise to new forms of leadership. I am not totally comfortable with this. While I believe that private initiative is key to development, I also believe that without the active participation of youth in public policy, the opportunities for social change are severely limited.

But the lack of youth engagement stemmed from more than just their lack of interest. Traditional elements of the political class resisted creating space for new leaders. It was a sharp contrast to the private sector which had welcomed the emergence of a new group of entrepreneurs and enterprises.

As a result, young people are more reluctant to participate in politics. The new generation still holds a favorable opinion of democracy, but it is on the decline. (According to the LAPOP surveys cited in the “Charticle” in this issue, 72.5 percent of Nicaraguans between the ages of 18 and 35 support democracy.) In an environment in which there are few opportunities for new leadership and many of Nicaragua’s more talented and better educated youths are avoiding political parties, the deteriorating faith in democracy is understandable—and likely to get worse.

Soon after I returned, I began working as an organizer for a war veterans’ cooperative, and like many social activists, I was considered somewhat eccentric. My family and friends wondered if I knew what I was doing. But today, working in civil society is regarded as an important field. For the past decade I have been organizing and educating young people in civic activism for nongovernmental organizations. Although I sacrificed some economic security—such work is not well-paid and is always precarious—any doubts I may have had about my decision were erased on November 21, 2008. On that date, Nicaragua’s civil society organizations came together peacefully to mobilize more than 80,000 people in the streets of Managua to protest municipal elections conducted under questionable circumstances.

Our protest demonstrated that civil society can have a major impact on Central America. It used the only wealth we have—social capital—to secure a seat at the table where our political and social future is being decided. And it proved that social action can be a powerful force for the development of a better life for our peoples. I hope that this lesson will not be lost on young people in our region, and in the rest of the hemisphere. By raising our voices and acting together for a better future, today’s Central American youth will repay the debt that our generation not only owes to history, but to all those innocent and vanished voices silenced by our tragic decade of war.

Cortesía: Félix Maradiaga blog

Foto Cortesía: La Prensa

Félix Maradiaga: Líder nicaragüense pro derechos humanos se quedará en EE. UU. ‘por algunos días’ más

Profesor universitario denunció en Washington torturas a estudiantes; gobierno lo liga con supuesta organización criminal.

Profesor universitario denunció en Washington torturas a estudiantes; gobierno lo liga con supuesta organización criminal.

Félix Maradiaga, profesor universitario y reconocido defensor de los derechos humanos en Nicaragua, confirmó a La Nación que no regresará el lunes 11 de junio a su país, como lo tenía previsto, y aseguró que se quedará “por algunos días” más en Estados Unidos.

El activista tiene orden de captura porque el gobierno de Ortega lo liga con una supuesta organización criminal financiada por el narcotráfico. Sin embargo, Maradiaga alega que la denuncia es parte de una estrategia del gobierno para desprestigiar su trabajo y las protestas estudiantiles.

En declaraciones al diario La Prensa de Nicaragua aseguró que no regresará “por falta de garantías a su vida”.

“Reitero mi decisión de regresar a Nicaragua en los próximos días. Sin embargo, luego de un profundo análisis con fuentes muy serias, no existen las condiciones para volar a Managua. No quiero poner en riesgo ninguna vida ni permitir que mi arresto se convierta en un circo que distraiga a la sociedad nicaragüense de la verdadera causa que nos moviliza”, manifestó a La Prensa.

¿Quién es Félix Maradiaga?

Mariadaga es director del Instituto de Estudios Estratégicos y Políticas Públicas (Ieepp), reconocido defensor de los derechos humanos y líder político en su país.

Maradiaga estudió en la Universidad de Harvard donde obtuvo una maestría en Administración Pública; en la Universidad Mobile en Alabama, donde se licenció en Ciencias Políticas y estudió en otras prestigiosas universidades estadounidenses. Además, en el 2015, la revista Forbes lo declaró una de las 25 personas políticas más influyentes de Centroamérica.

Cortesía: La Nación (Costa Rica)